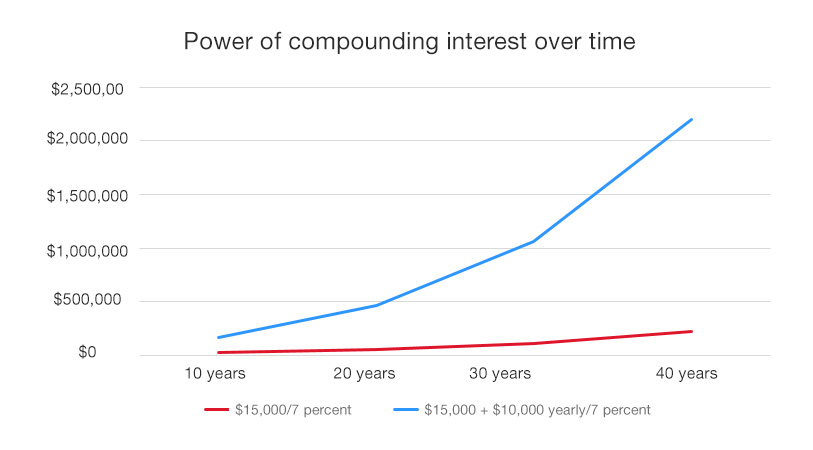

As example one shows, if your child invested $15,000, they would have over $200,000 in 40 years at the 7% return level. If your child invested a bit more each year, as shown in example two, the outcome would prove even more exciting. By investing only $415,000 over 40 years ($15,000 original investment plus $10,000 additional per year; that is, $10,000 x 40), they would have over $2 million at the 7 percent return level.

3. You gain the potential to fulfill long-term financial goals

Investing is about making money grow to meet long-term goals rather than cover immediate or short-term needs or desires. As an example, if your child wants to buy a new video game when it comes out in a few months, they should focus on accumulating money in their savings account. However, if they hope to buy a car, indulge in travel, own a home or become a philanthropist one day, investing in stocks, bonds or mutual funds that pay dividends and income — and that can appreciate over time — may be more appropriate.

As a caveat to investing’s potential, it’s important to explain about risk and its relationship to reward. For example, the money in bank savings accounts has virtually no risk, but the reward is low. On the other hand, investing in riskier assets may allow their money to grow more over time. However, risk can be unpredictable and can affect returns, especially over the short-term.

3 steps for children to put investing principles into action

1. Open a brokerage account

Opening a brokerage account in your child’s name can provide a great vehicle for ongoing communication about essential financial concepts, personal goals and family values. Many parents opt for a custodial account like a Uniform Transfers to Minors Act (UTMA) or Uniform Gifts to Minors Act (UGMA).

Your child owns the money, and you will control the account until he or she reaches the age of majority (varies by state). Because the money will belong to your child, income and gains may be taxed, at least partially, at your child’s rate, which is generally lower. Money spent out of this account needs to be for the benefit of the child.

Creating opportunities to teach your kids these basic investing principles, and then helping put the principles into practice, can be an important step toward their eventual financial independence.

An alternate option is a guardian account, in which you own the money. You can withdraw it for any reason you want, and you’re the one who is liable for the taxes on the earnings at your own tax rate. Ask your financial professional for more details about how these accounts might affect your individual situation.

2. Figure out how much to invest

After you’ve opened your child’s account and reinforced the key concepts, such as the value of investing over the long-term, the next question is how to proceed. Many parents start with a small gift to the account to get things started.

Next, consider helping your child determine the amount of money from allowance or savings they’ll need over the next six months. They should hold that money in a savings account, with the rest available for investing. This exercise can help children understand how budgeting, savings and investing can work together.

3. Decide on an investment strategy

Once your child knows how much they want to invest, it’s time to decide how to invest. One approach is to allow kids to buy individual shares in companies they know and like. Explain that owning shares of companies that make smart phones, gaming equipment or your favorite soda means that every time these companies sell their products, they are creating profits for their shareholders — and now your child is one of them. Profits generated by these companies can come back to your child, the investor, in two different forms: through the appreciation of the stock price and/or cash returned in the form of dividends.

An alternate approach is to teach children how to build a diversified portfolio. While this may not be as exciting as owning individual shares, it can certainly be less volatile. The up-and-down cycles of a diversified investment portfolio will be less severe than owning just one or two stocks and may be less likely to cause your child to become disillusioned with investing.

Exchange traded funds (ETFs) are a popular low-cost way to get exposure to multiple stocks with a single easy trade. For example, you can explain that owning an ETF of securities in the S&P 500 means they own small pieces of 500 companies. There are also various mutual funds directed to children, or you can mix in an ETF that focuses on fixed income so they can see how stocks and bonds work in tandem.

Teaching your children to invest can be both educational and fun. By getting them interested in investing early, you’re buying more than stocks and bonds. You’re helping your children learn financial skills that they can use for a lifetime.

Learn how Ascent Private Capital Management of U.S. Bank works with the next generation of family leaders.